Cash Party Is Almost Over for Unicorns Like Uber: Shira Ovide

2019-04-11 12:00:21.716 GMT

By Shira Ovide

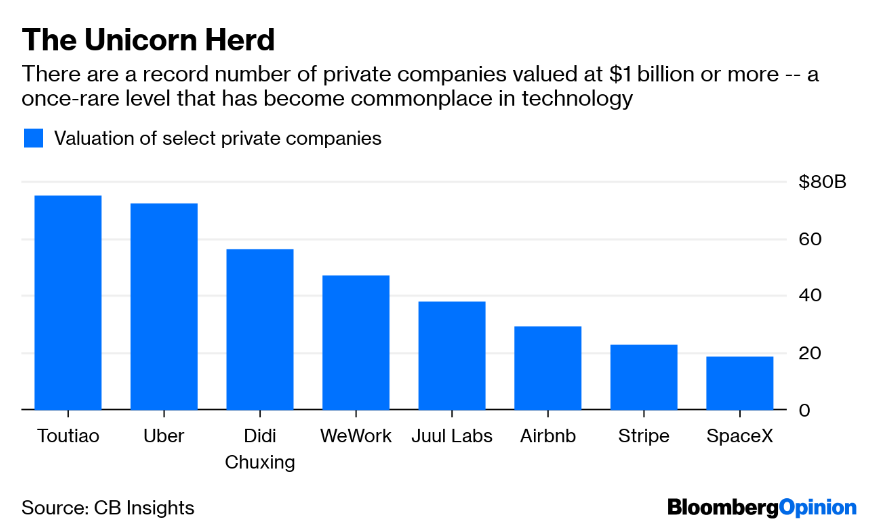

(Bloomberg Opinion) — Uber Technologies Inc.’s coming IPO

is a moment to reflect on the oodles of investment cash that

have resulted in a herd of “unicorns,” the awful but convenient

shorthand for tech companies that reach valuations of at least

$1 billion while they’re private.

There are now more than 340 of them, according to CB

Insights, compared with the 18 unicorns identified in 2013 by

investor Aileen Lee when she coined the term. (Her list had 39

companies, but many of them had already gone public or been

acquired. Uber was on Lee’s list even back then.)

This unicorn proliferation is a result of changes in

technology and investing, including a decade of low U.S.

interest rates that pushed investors to hunt for better returns

in riskier, high-growth assets including tech startups. Last

year was the first time since 2000 that U.S. venture investments

in tech startups topped $100 billion, according to figures from

the National Venture Capital Association and PitchBook. It was

the capstone — so far— to what has been several years of

eyebrow-raising amounts of capital going into startups

worldwide.

A defining characteristic of the unicorn years is the

importance of investment cash. Winners and losers are determined

in part by which companies can raise the most money, not

necessarily the ones that create the best product or service.

Uber is the perfect encapsulation of this trend. Money was

a big way Uber differentiated itself from Lyft Inc. Its big bank

account dictated Uber’s strategy of going global and splurging

into adjacent categories such as restaurant food delivery and

freight handling, while Lyft stuck mostly to on-demand rides in

North America. There would be no Uber, or at least not one of

this size and breadth, at any other time in history.

That’s not to say that Uber’s product or its strategy is

inferior to Lyft’s, but the company was able to dream bigger

because it had more access to capital. At some point,

availability of cash becomes self-fulfilling. The startups that

look like winners get more capital, which ensures they win.

Whether that’s good or bad is up for debate. The elite

startups of the 2010s including Uber, Didi Chuxing Inc. and

SpaceX are bigger, more disruptive and potentially more lasting

companies because they had limitless access to cash to grow.

But the venture capitalist and Lyft investor Keith Rabois

recently told my colleague Emily Chang that a large amount of

investment money “usually creates more problems than it solves”

for startups. This is not a new idea. There’s a Silicon Valley

axiom that the best young companies tend to grow up during

recessions, which forces them to spend wisely and make sure

they’ve honed their products.

Regardless, now that some of the biggest unicorns such as

Snap Inc., Lyft and Uber are starting to go public, it may be

the beginning of the end of the period in which startups

differentiated themselves on fund-raising ability.

Not the end-end, of course. Electric scooters continue to

be a capital-raising race. So does restaurant food delivery, in

which Uber is playing the role of market share-grabbing, cash-

burning entrant.

One thing that won’t change as the elite unicorns go

public: They’re still wildly unprofitable and will be for some

time. But from now on, fewer unicorns will be able to rely on

the gushers of investor cash on which they’ve built their lush

magical forests.

A version of this column originally appeared in Bloomberg’s

Fully Charged technology newsletter. You can sign up here.

To contact the author of this story:

Shira Ovide at sovide@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net